The Public Lab Blog

stories from the Public Lab community

About the blog | Research | Methods

Northeast Barnraising 2018: How to Make Disasters Less Disastrous #Barnraising #crisisconvening

This Northeast regional Barnraising was like no other because it started with people exchanging stories of disaster. It was an appropriate ice breaker since the first day was dedicated to crisis convening. I shared my experience of an earthquake that hit while I was at a café in Philadelphia. I remember my inner dialogue went from "possible subway work" to "nearby construction" to the gut instinct that this was an earth shaking event. How much time did I lose arguing with myself? What would I do differently next time? As others shared their encounters questions arose: How many people have experienced natural disasters? What does emergency relief look like? What should it look like?

It's hard to compare a small earthquake that merely puts people on edge, to a hurricane with flooding that causes loss of homes, jobs, food and electricity. Testimonies from flood survivors, (who I'm now renaming flood wranglers) provided details of rising waters and destruction in so many communities---New Jersey, Texas, Florida, El Salvador and Puerto Rico. I know I was swept by the emotions of sadness, fear and anger hearing about their situations. Yet there were also stories of community leaders, bartering and rebuilding that brought hope. After another day of Barnraising, the stories started to sound similar. In fact, you could have exchanged locations and faces, but the same problems were surfacing.

- People were not being helped

- Governments were failing to respond efficiently (or not at all)

- Communications failed

- Systems were not in place for food and water

The greatest thing about a

Barnraising is that it not only provides a safe place to discuss problems, but

it also encourages sharing current solutions while working on new ones. One of

the best tools I heard presented was the common bicycle. They can be

used for transporting supplies and medical aids, as they are

nimble when most roads are jammed or impassible. Bikes are also able to be

hacked to become generators to recharge phones--that's something everyone

should have in place!

One of the sessions that got

me most excited was creating a "Communication Checklist". Solid ideas were put

on paper about the best ways to communicate during a disaster when electricity

fails. Details include using flyers with bold/cultural images to communicate

meeting places and times, connecting with community leaders, using libraries as

hubs, encouraging face-to-face communication and supplying printouts of

resources.

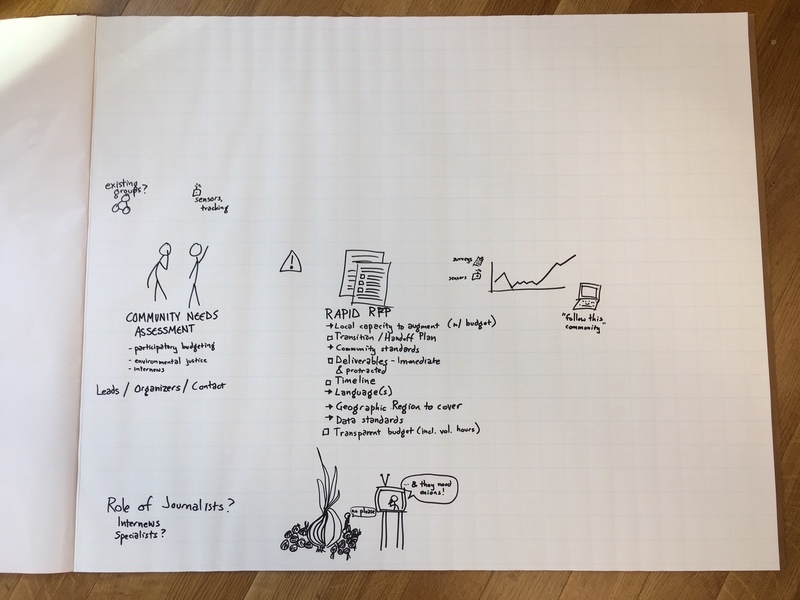

Choices of resources are often not controlled by communities, and one session addressed that problem by creating a blueprint for a Rapid RFP (Request for Proposal). It includes a transition/handoff plan, deliverables, timeline and transparent budget. This entire process would help to ensure that a community receives the right help it needs and would also put into place a checks and balances for how the process is working out.

Checks and balances is probably just the shadow of what I encountered on this Barnraising. The most memorable part was hearing quavering voices as truths were shared across all disasters including government mistrust, racism, receiving inappropriate supplies, neglect, hunger, sickness and homelessness. Still these discussions are so fresh in my mind and I'm so thankful for those that were able to stand up in front of the group and be so honest. We need to hear this---the world needs to hear this. So, what can we do to make disasters less disastrous? Here's what I learned so far:

- Start making connections with your community now to prepare---leaders and resources

- Despite mistrust, we must work to communicate with government so they become partners

- Have a plan of action for your household and family members including supplies

- If disaster strikes a community other than your own, make sure you are invited to help by the community or from a trusted resource of that community. The history of the community is an important consideration and a great example can be found on this post about the situation in Puerto Rico.

- Money doesn't solve the problem in larger disasters---be ready to barter and share

- Use the connections made at Barnraising to boost our network and join to help

We cannot escape that all things are interconnected and I know that I'm still learning how to ask for and accept help. For those that attended the Barnraising, please do add in your thoughts on what you learned or what could be helpful in a disaster. I remain in awe of flood wranglers and those serving in disasters.

Follow related tags:

barnraising newark blog northeast

The fight to get out of Pascagoula

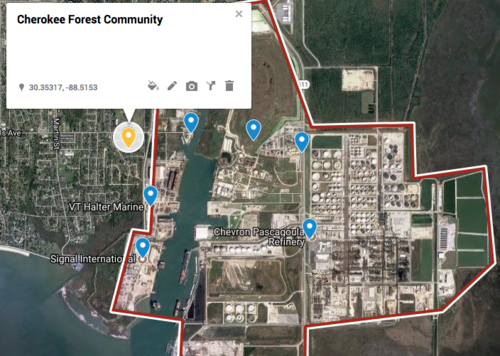

Pascagoula, Mississippi hosts 12 facilities that report to the federal Toxics Release Inventory, six of which are within a mile-and-a-half radius of the Cherokee Forest Community (2016 Reported toxic release data here). Below is the story of Barbara Weckesser, and her struggle to get out.

Barbara Weckesser:

“Today, I couldn't sit outside for all the noise. We itch all the time. My eyes burn all the time. People who move here get sick. The children who were unhealthy here move away and seem to get better. My husband’s health conditions have gotten worse here. It has been a nightmare. I’m wondering how quick can I get bought out, and get out of here?”

On monitoring

Over the past couple of years we’ve done all we can think of to document our concerns and share them with the “right people.” We got the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) to come in and do some testing. They came out three or four times, and each test shows something in those air canisters, even though none of the tests they did were done the way they were supposed to; they didn’t leave them out for the required 24 hours, and they all came back with stuff in them.

A while ago, Mississippi Phosphates agreed to put in a monitor and within three days it showed that there was sulfuric acid in the air, and two or three days after that, again. Then, for 28 days that the monitor read “over.” MDEQ’s response to me was “Oh, it was turned off. That’s why it read over.” It wasn’t off; the monitor was reporting sulfuric acid. We have all that data. But when MS Phosphates went belly up, that monitor went belly up too. (Mississippi Phosphates closed and their former site is now listed on the Federal Priority List as a Superfund site.)

We keep odor logs. I’ve got a book, it’s about 13 or 14 inches thick, and it’s by the date for when we’ve written odor reports. I’ve also paid for tests myself. We’ve done particulate matter monitoring and have gotten elevated levels, and we’ve paid for bucket air sampling as well. Each time it shows something in it, but each time they say it’s not something that’s going to hurt you. But when you look at the cancer rates around here, and the number of people who have passed away from cancer just in the past year and a half, something is causing it.

Most of the tests we’ve done have been for particulate matter because that was the cheaper test to do, but that doesn’t capture the chemicals. We want to target the pollutants coming from Chevron, and the bucket sampling can do that, but it requires that you take the samples and get them in the mail right away. It’s not easy to do. It’s too time- and energy-intensive, and too expensive.

On permits and public pressure

We’ve gotten our test results in a public meeting on record. I wanted to use it as a way to put pressure on the new mayor. He promised he would get us out of this situation. Let’s see if he holds it up.

MDEQ said “hit them on their permits” and made us all go to permit training. I said sure, I’d love to hit them on their permits, but we can’t take them on on account of their permits because MDEQ hasn’t made them follow through to renew them. Why is our government letting these companies operate without permits, without them being renewed? They’re not bringing these renewals up for public comment, and even when they do, we comment and nothing changes.

On next steps

Here we sit, our hands are tied, and they can pretty much do what they want to unless we can find something that we can bring them all in on. And the one thing we can bring them all in on is health. Right now, we’re working on starting up a health survey with Dr. Wilma Subra. We’re also working with an attorney, but the work he would need to do is really expensive. It would be great to have an inexpensive and easy way to prove these chemicals are in the air here. I would also love to have some legal environmental health advice for what else we can do to bring these companies to the table to say, “Yes, we did that. Yes, we will work with this subdivision to get them out.”

Follow related tags:

gulf-coast mississippi blog pollution

Public Lab partnership with NASA AREN project brings new easy-to-use tools for classroom use

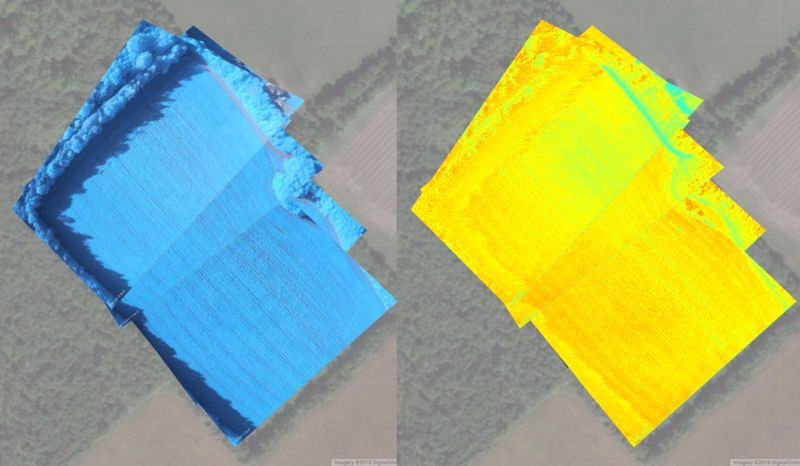

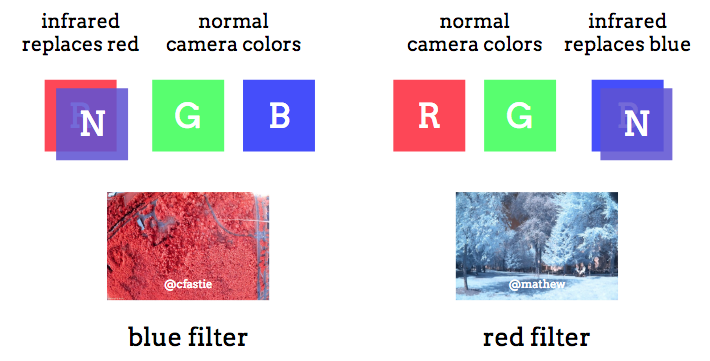

Since 2011, Public Lab community members around the world have been building and using modified consumer cameras to take multispectral photographs, enabling thousands of people around the world to explore the world around them using vegetation analysis tools such as #NDVI. As illustrated above, comparing infrared and visible light can offer clues to plant health, and DIY cameras like Public Lab's can make this kind of analysis possible on a very small budget.

(this post was cross-posted on the Globe.gov blog)

You can see just a few of these on Infragram.org, and in the new (beta) NDVI tool in MapKnitter.org. Here, DIY aerial infrared photos of a farm in Canada can help reveal healthier and less healthy areas of crops:

Building on an initial low-cost technique for modifying consumer cameras to take multispectral photographs (by switching a filter behind the lens), Public Lab community contributors have developed a suite of web-based multispectral analysis tools to lower barriers and engage members of the public in using these techniques for the analysis of agriculture, land use, runoff and water quality, wetlands restoration, urban planning, hydroponics, and many other applications.

Now, in partnership with the AREN project at NASA and in collaboration with the GLOBE program (and with support from Google Summer of Code), Public Lab is now developing a set of in-classroom materials and resources for students to learn about earth observation and image analysis in an experiential way, from constructing their own multispectral cameras to using the free and open source spectral analysis tools provided by Public Lab. These images show the two types of single-camera modifications - one resulting in a blue-toned image, and one in a red-toned one. It's also possible to do this with two cameras.

If you teach in or out of a classroom and are interested in how remote sensing, satellite imaging, or vegetation analysis could be part of your education work, we're eager to work with you!

Learn more at PublicLab.org/infragram and check out our starter kits for modifying cameras at https://store.publiclab.org/collections/diy-infrared-photography

Follow related tags:

balloon-mapping near-infrared-camera ndvi education

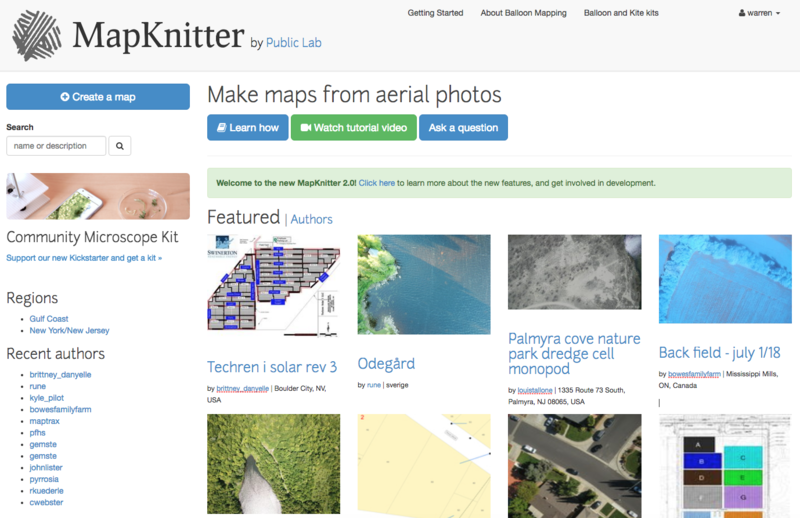

New accessibility features for making aerial maps in MapKnitter

Map-making with your aerial photos is an important part of balloon or kite mapping. It's like making puzzles -- SOME people really love it and SOME people really don't!

MapKnitter -- now entering it's 9th year as a free and open source project hosted by Public Lab -- has slowly been getting upgrades and refinements that make it easier to use.

We've just posted an update that made MapKnitter more accessible, with new differently-shaped handle icons that also work on tablets, where map-making can be more collaborative. See it in action in the GIF above.

We also made the handles larger, which makes it easier to use on a tablet -- iPads make for a great way to get a group together and stitch a map in a group.

Give it a try at MapKnitter.org!

...or if you're working on your own mapping projects and want to use just the distortion component, check out our stand-alone library, Leaflet Distortable Image:

https://github.com/publiclab/Leaflet.DistortableImage

**Update **I also wanted to highlight that 2 different first-time contributors helped make this latest version possible!

Thanks to Nana Adjedu and Jason for their help in completing this update!

Follow related tags:

balloon-mapping mapknitter blog leaflet

Community Microscope-- THANK YOU

Thanks to the 357 supporters of our recent Kickstarter campaign, the Community Microscope will soon be shipping to community scientists, environmental investigators and advocates, teachers and learners, artists, makers, and lots of other folks who got involved with making this project happen.

Over the course of this campaign we were lucky to work with people from within the Public Lab community who chimed in to offer suggestions, support, criticism and refinements. Everyone's work and care for this project has given us the chance to introduce new people to our work-- though events at two different Maker Faires (Bay Area and Providence), a workshop at the Nueva School, and through lots of social media and real-life conversations with people who are getting excited about the world of possibilities available to them with open source tools.

We wanted to thank everyone who made this possible, in full open source spirit -

- Our collaborators in Wisconsinhttps://publiclab.org/tag/wisconsin

- the Hackteria networkhttp://www.hackteria.org/

- Lifepatch in Indonesiahttps://www.lifepatch.org/

- Max Liboiron and the CLEAR labhttps://civiclaboratory.nl/

- Parts & Craftshttps://partsandcrafts.org

- WaterScopehttp://www.waterscope.org/ and the Open Flexure Microscope teamhttps://github.com/rwb27/openflexure_microscope

- Our Google Summer of Code fellow MaggPihttps://publiclab.org/profile/maggpi

- And so many more!

We're already starting work to get the Early Bird kits shipped; stay tuned on Twitter and Instagram to see our progress, and get ready to #RemixTheMicroscope!

Keep your eyes open for more documentation and activities going up on the Community Microscope page on Public Lab's website in the coming weeks and months as this project continues to grow!

THANKS!!!

Follow related tags:

kits kickstarter blog with:warren

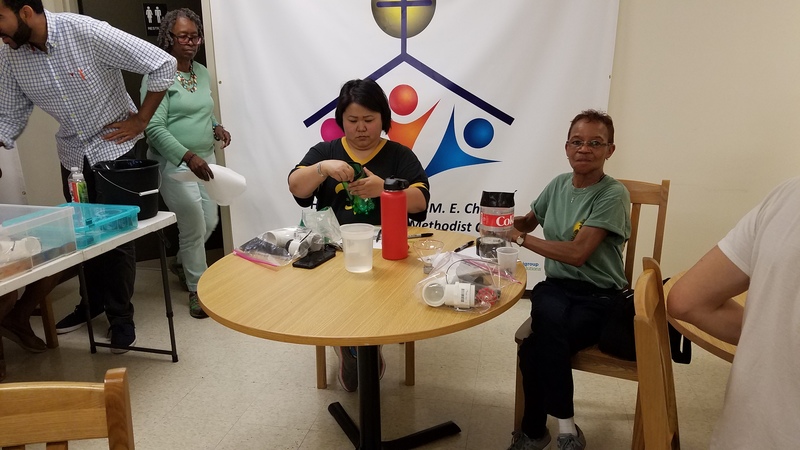

Rain Barrel and Rain Gauge Build with 7th Ward Residents

This past weekend, Public Lab and Recharge NOLA, with Water Wise 7th Ward, led a joint workshop to build rain gauges and rain barrels with New Orleans 7th Ward residents at Dillard Community Resource Center. Over the course of the event, 20 participants worked to build 11 rain gauges and 11 rain barrels.

For the first part of the workshop, participants shared ideas and examples for why rain gauges are useful and important. For example:

- In New Orleans, rain data comes from the airport, which often doesn’t reflect more localized rain data.

- The rain gauge can help people figure out how much rain it takes accumulate stormwater in a local area and cause flooding.

- The gauge can also help us to know how much water is in a rain barrel after a rain event.

We then used instructions based off of these materials to consturct rain gauges together.

This was the first time I had done this workshop, so gathering edits and ideas for the instructional materials was really helpful. For example the materials need to explicitly say that the gauges need to sit on a flat surface when people are drawing the lines, and that using food coloring in the water can make the water line easier to see. Participants also brainstormed ideas on how to set the gauges up outside after the event, for example we discussed options around signposts, zip ties, hose clamps, and even flower pots.

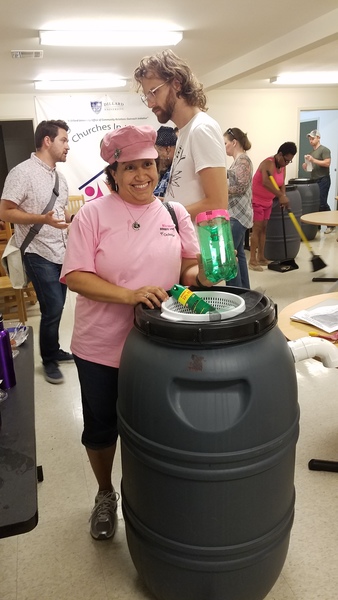

In the second part of the workshop, Hilairie Schackai with Recharge NOLA, a partner of Water Wise Water Wise used materials she had put together ([available here] (http://bit.ly/DIY_RWH_WaterWiseNOLA_updated11-22-15)) to explain the importants, and the various uses of rain barrels. She then walk participants through constructing their own barrels.

I had never participated in a rain barrel workshop before and some of the important takeaways I had from the experience were that:

- The barrels need to be emptied after each rain event, so they are useful in helping to reduce stormwater runoff during the next storm.

- It’s important to use screen materials over the holes on the rain barrels to keep mosquitos and their larvae out.

- While rain barrels are fun and useful in thinking about alternative uses of stormwater (watering your lawn or garden, washing cars, and generally reducing your water bill), they also significantly reduce the amount of water our stormwater system needs to handle in a rain event. The data Hillarie about the relationship between rain captured and flooding was staggering - read her materials!

Follow related tags:

gulf-coast event new-orleans blog