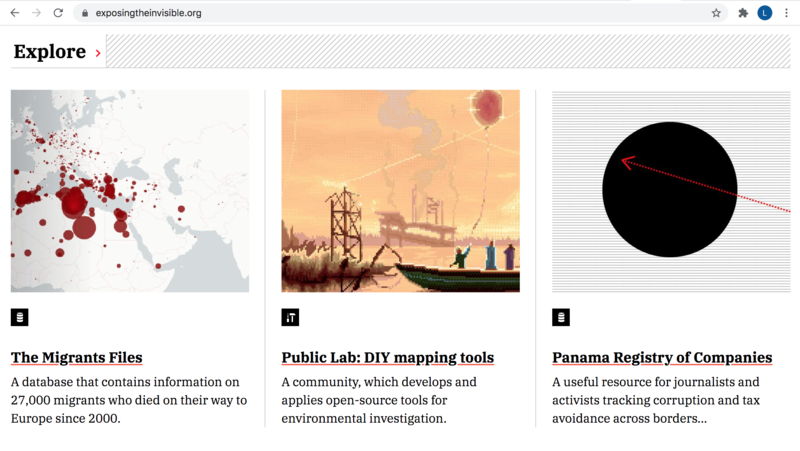

Community science might sometimes be described as "collaborative investigations for accountability" — a phrase also used by journalists. Into this space of overlap comes this great guide to #OSINT or open source investigations: Exposing the Invisible - The Kit. The Table of Contents is nice, too. A project by long term comrades, https://tacticaltech.org/!

The following points about evidence are excerpted from https://kit.exposingtheinvisible.org/en/investigation-concepts.html

Your checklist for good evidence

Not all evidence is good or relevant. There are some qualities that distinguish what is “good” and useful for your investigation. The best way to make sure you are on the right path is to test the strength, accuracy and integrity of your information, and to ask yourself a few guiding questions.

- Good evidence is first-hand. Did you witness something yourself; do you have access to the persons involved, or to official documents about it?

- Good evidence can be documented and preserved. Are you able to map the path that led you to the evidence, record every step of your research process, and save it in a way that other investigators can later access it, confirm its accuracy and make sense of it?

- Good evidence is timely, created or documented close to when the event occurred. Did a lot of time pass and make the evidence less traceable? Did recordings or documents get lost? You will need to dig up the past or find new information elsewhere.

- Good evidence can be verified. Can you and others check and confirm that what you have is real and accurate?

- Good evidence has origins that can be confirmed by a third party, in addition to you and your source. Are you the only one who has access to the source of information, and the only one who can say it is real? If so, this can become a weakness if someone should challenge your evidence or claim you are making it up. However, if you are dealing with a vulnerable source, keeping it a secret may be your - and their - only viable option.

- Good evidence contains information that can be confirmed by a third party. Is there anyone or anything else that can support your claims and evidence? An expert, another witness, an organisation doing research on the issue, an official document. The more, the better.

- Good evidence can be shared with other people. Are you able to show this evidence to support your arguments and claims, or is it confidential and therefore needs to stay undisclosed? If that’s the case, you might need additional ways to prove to others that what you are saying is true.

- Good evidence has a documented, unbroken chain of custody. Did you log every step of your research process? Did you save all findings with exact source details, dates, times and places where you found the information? Did you save all the information safely and make sure it never left your hands, was not tampered with and you can always trace everything back to its original source?

- Good evidence is uncorrupted and kept safe from tampering. Can you make sure that nobody unwanted has access to it and can modify it in any way?

- Good evidence includes metadata such as information about its author, location, time. Can you confidently say that you know a photo or a video was taken where the source claims it was, when it claims it was, and shows what it claims it shows? If you collected the evidence and recorded the images yourself, can you prove their authenticity by preserving their metadata? Any lost metadata can be a weakness to your evidence later on. Make sure you keep it safe.

- Good evidence connects to other pieces of evidence and links information together. Can you connect your evidence with other information and findings from more sources to support your argument or create a stronger narrative about the issues you are investigating?

- Good evidence will direct you to places where your information is weak or incomplete. Does it open up more questions, show you information gaps and new ways to seek additional evidence? That is a good thing, it will help you gain a better overview of the issue and ultimately build a stronger argument.

- Good evidence doesn’t expose human sources to risk that the investigator can’t manage. Could someone directly or indirectly link your evidence to a vulnerable source whom, if exposed, may be in danger? If yes, can you reduce those risks in any way to protect that source? Is there any way to find other evidence, which supports your narrative but does not expose the potentially vulnerable source? If not, you may need to reconsider using that evidence and put the safety of your sources and of yourself first.

- Good evidence may challenge your preconceived ideas or even contradict what you think is true. Does it show that your expectations or arguments aren’t valid? Does it make you see a problem from a different perspective, or even totally change your mind about an issue? Did you believe a source but ended up doubting it once you analysed more evidence from other sources? This is a good thing, and by admitting and accepting it, you are becoming a better, more impartial and hence more trustworthy investigator.

- Good evidence speaks for itself. Can you just show what you have and be confident that people will understand the information and its meaning? Or do you still need to build a larger picture or a narrative to boost it?

Not every piece of evidence you discover will meet all these conditions. That’s to be expected. But some of the evidence you find will meet a lot of them – those pieces are the ones you may want to prioritise.

The points above on evidence are from https://kit.exposingtheinvisible.org/en/investigation-concepts.html

Bonus appreciation

https://exposingtheinvisible.org/ directs viewers to publiclab.org <3

What do you think?

Did any of the points about evidence resonate with you? Please share in the comments - we'd love to hear your stories.

0 Comments

Login to comment.