A Space for Everything, but not Everything has a Place

During my time with Public Lab, we have been photoing the Restoration of Bayou St John, a saltwater stream. It helps to know the recent history of the Bayou to interpret the colors in our pictures. After the Bayou fell out of industrial shipping use, the Levee Board governing its borders saw the Bayou only as a hole in the levee-armor around New Orleans, and sought to block it with a roadway and earthen wall across its channel.

The Bayou was a void, and flow of water was contrary to the Board’s purpose. Was the Bayou Trash?

New Orleanians did not think so, and sued the Levee Board to halt the completion of the road (made of sand and the shell bodies of local clams) and to stop a levee from damming the Bayou completely. Instead of a levee an expensive gate was installed. A gate could, theoretically, be opened. Residents “won” their legal challenge against the government, but the gate sat permanently closed by a Levee Board unwilling to fund its operation. Without an operational plan, was the gate trash?

Trash as a Thing-in-a-Place can Displace an Ecological Function

The never-ever used roadway in the channel of the Bayou definitely was trash, and the Wildlife agency (LDWF) made a restoration plan for Bayou St John that included opening the gate and re-excavating the road to make a Bayou channel to restore the flow of oxygen, nutrients, and plants and animals from Lake Pontchartrain. LDWF had to remove the trash to restore the Bayou.

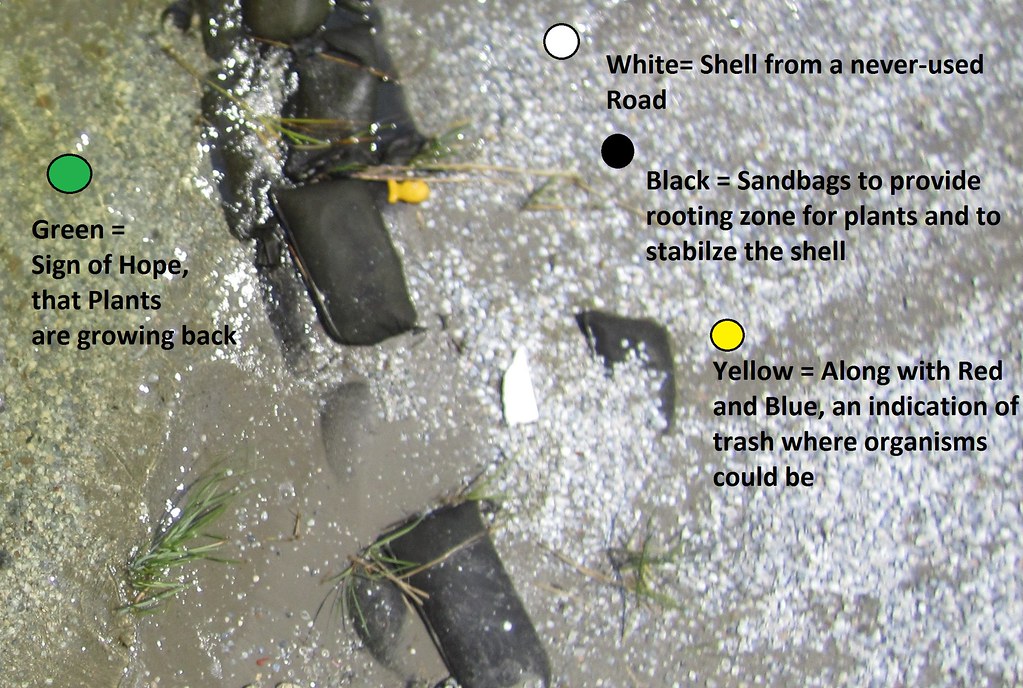

The roadway was excavated, but now what to do with the clamshell-that-had-been-road? LDWF needed to remove the material, but non-profit advocates saw wetland where LDWF just saw trash. Andy Baker of the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, working with the contractor, and special plant-friendly sandbags, got some sand and roadbed material placed as a marsh platform, turning trash into a home for plants, to increase the ecological potential of a restored Bayou.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/healthygulf/14918036902/sizes/o

trash is visible on the natural landscape of green and brown, if it is white, yellow, blue or red

As always, the unexpected has happened. The contractor left piles of road shell beneath the bridge as tropical storm Karen passed and Karen pushed this unwanted shell into part of the restored channel. This trash shell is now migrating as spits that threaten to cover the newly-planted marsh grass at Bayou St John. PublicLab has been monitoring these spits as they have passed, and our monitoring has moved Andy to proactively stabilize re-shape them before the shell smothers our precious marsh plants.

Unwanted guests, unexpected benefits

Furthermore, since the channel has been returned, the bayou marsh is filled with traditional trash--the ubiquitous plastic that floats in an urban lake. Improving the drainage of Lake Pontchartrain into the Bayou has created a funnel for plastic bottles, household waste from storms, and even plastic fish where we wanted real fish to swim. Is the “restoration” site a failure, or an unexpected success?

“Well, you could look at it as a downside," says Andy Baker, “Or you could say we’ve created a place that naturally traps the plastic in the Lake, and makes it easier for us to clean things up.” The Foundation sponsors an annual “beach sweep” where volunteers pick up trash around the entire Lake.

And so, the ecological restoration of flow, oxygen, nutrients, and life to the Bayou will also serve as a conduit to remove the plastic trash that dominates urban life.

0 Comments

Login to comment.