near-infrared-imaging

Infrared photography for vegetation analysis

Infrared photography can help assess a plant's health. Infrared imagery for agricultural and ecological assessment is usually captured from satellites and planes, and the information is used mainly by large farms, vineyards, and academic research projects. For example, see this illustrated PDF from a commercial imagery provider who has been studying the usefulness of infrared imagery and has quotes from farmers. There are public sources of infrared photography for the US available through the Department of Agriculture -- NAIP and Vegscape -- but this imagery is not collected when, as often, or at useable scale for individuals who are managing small plots. By creating a low-cost camera and working with farmers and environmental activists, we hope to explore grassroots uses for this kind of technology. What could farmers or activists do with leaf-scale, plant-scale, lot-scale, and field-scale data on plant health if the equipment costs as little as $10 or $35?

Screenshot from 2011-09-10-colorado-boulder-foothills-community-park-NRG. See how clearly plants are identifiable from bare earth or pavement. The unique colors in this photo will be explained below, keep reading!

Why does it work?

Though we cannot perceive it with our eyes, everything around us (including plants) reflect wavelengths of light in red, green, blue and beyond into infrared, ultraviolet, and more. Our colorful world is created by varying amounts of particular wavelengths being absorbed and reflected. This also means that everything has a recognizable "spectral signature". Whoa.

Plants use visible light (mainly blue and red light) as 'food' -- but not so much green light, which is why they reflect green away, and thus look green to our eyes. They also happen to reflect near infrared light (which is just beyond red light, but not visible to the human eye). This is because they chemically cannot convert infrared into usable food, and so they just bounce it away to stay cool. The illustrations show what colors of light plants absorb versus reflect away.

By using this unique property of plants, plus our ability to take near-infrared photos we can create composite images which highlight where plants are and how much they are photosynthesizing.

Learn about NDVI images and how they work

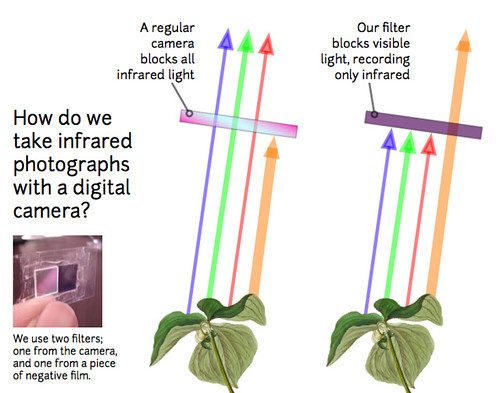

We've been modifying cheap cameras to photograph in infrared (IR). The sensors in common digital cameras are sensitive to infrared, but come with a filter that blocks these wavelengths so that the photos look "normal" to us. Removing that filter allows us to pickup information in IR, and in that way begin to "see the invisible life of plants."