This post was originally featured on the PBS MediaShift IdeaLab blog as "DIY spectrometer project seeks affordable contaminant analysis"

The Public Lab community has been working on a cheap, open source spectrometer for detecting environmental contaminants for some time now. Since the last spectrometry update a year ago, a lot has happened, so I thought I'd take the opportunity to write an update on the project. Most importantly, we've just launched a Kickstarter campaign to actually get spectrometers into peoples' hands -- lots of them. For as little as $35, you can now get your own kit and start scanning different materials in your backyard, neighborhood, or household. With one of our latest prototypes -- a spectrometer that attaches to your smartphone (see above image) -- we hope to make spectrometry available to anyone, even when you're outside or away from home.

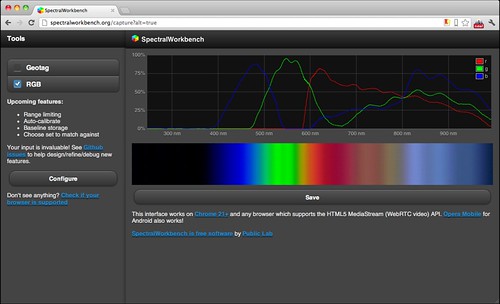

In creating a disruptively inexpensive and accessible instrument -- at under $100, while commercial spectrometers are thousands, or tens of thousands of dollars -- some of the key challenges involve calibrating data and assuring that it is good enough quality. Where we left off, we were testing different ways to calibrate, standardize and compare spectral readings. Now, having made much progress (though there's still much to be done!), we're focusing on a different part of the problem -- data collection and experimental setup.

(Above, the "countertop" model available on Kickstarter)

(Above, the "countertop" model available on Kickstarter)

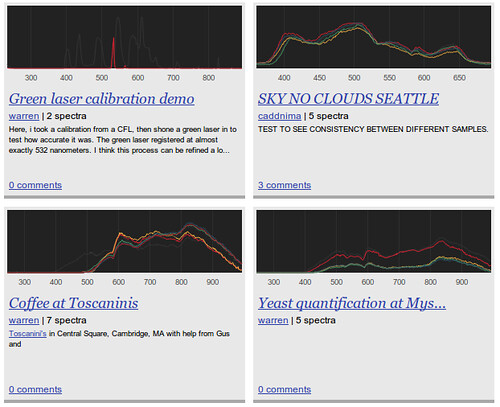

The hardware design of the spectrometer has progressed considerably and in pushing for so many people to build and use spectrometers, we're hoping to refocus efforts on building a shared, open source spectral library and developing easy, consistent, and rigorous techniques. In a sense, the project has progressed from an engineering problem to a science problem -- amongst the hundreds of Kickstarter backers, many are asking whether the device can be used for myriad applications, from agricultural testing of sulfur to blood or soil tests, to uses in astronomy or gemmology. I think it's great that people have so many ideas and questions -- that's the whole reason we're making this kit available, and it's a big step towards proving out different applications and methodologies.The science is really just beginning! For an overview of some of the suggested uses, see this wiki page on which we're starting to compile research: http://publiclaboratory.org/wiki/spectral-analysis

Though the many diverse uses might seem to distract from our original goal of detecting oil contamination, the open-endedness is intentional. We are, in a sense, gambling that by engaging so many new citizen scientists, the uses such as measuring grow lamps or laundry detergent dyes will help to refine and improve techniques which will benefit all uses, including pollution detection. Having a shared platform and standardized techniques, not to mention a whole community of burgeoning experts in spectral analysis, can't but help in bringing spectral analysis of pollution closer to reality.

We've made a few models of spectrometer available -- including a papercraft version for only $10 -- but the "countertop model" which comes in a nice enclosure with a dimmable lamp, is closest to the kind of device we imagine people will eventually put in their kitchen or garage, which restaurants or coffeeshops might have to test their products, or citizen scientists might use to quickly assess water or soil samples.

In that spirit, I've been visiting different spots around town to explore those kinds of everyday uses. Last week, I met up with Brian from Mystic Brewery, and we tried quantifying yeast in their propagator. A few days later, I visited Gus at Toscanini's in Central Square, Cambridge, and we scanned a variety of coffee drinks. Though this may sound like the nerdiest of foodie pursuits, I hope that we can inspire folks to learn about spectroscopy, a technique which today is available only to well-funded "experts" in university and industry labs.

Though our main goal is to make science tools available to non-scientists, there is much to be gained from attracting some scientists to our project as well. First, we've already relied on the contributions and advice of a variety of scientists in designing our tools -- from Public Lab contributors who work in spectral analysis to close examinations of NASA instruments like the CRISM spectrometer aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. But the very real possibility that traditional scientists would be interested in instruments 1/1000 the price of what they are used to can only help our cause by comparing and contrasting our tool's data to that of commercial alternatives. If papers are published which cite the use of our tools, credibility will grow, as will bridges between the science world and the wider public -- we just have to be sure the tools are good enough.

Finally, the analysis software at SpectralWorkbench.org -- a kind of OpenStreetMap or Wikipedia of spectral data -- treats spectral analysis like a "big data" problem. Though we web developers are now accustomed to thinking this way about leveraging huge datasets, the idea of a truly gigantic, shared, open source spectral database opens up possibilities for analysis and, of course, matching. We're being a little optimistic when, in our Kickstarter, we talk about building a "SHAZAM for materials", but we really hope that our growing community of self-taught spectral analysis experts will someday be able to hold up a spectrometer-enabled smartphone, scan a water sample, and confidently identify a dangerous carcinogen.

0 Comments

Login to comment.